2020 Atlantic Storm Names

June 1, 2020

Today is the official start of hurricane season in the Atlantic basin. We start the season with two names already marked off the list (See you in 2026, Arthur and Bertha!), For the first time since 2015 (and the last time for the foreseeable future), we do not have any new names on the roster. The National Hurricane Center issued its first regularly scheduled Tropical Weather Outlook this morning. As usual, it includes the list of names for this season along with their pronunciations. As usual, I have my notes on the past iterations of these names.

This year’s list was first used in 1984. Nine original names have been retired, which is the average (1981, with 11, holds the record for the most). As is the case for half of the lists, the name beginning with the letter I has been replaced twice. There are five names original to the list that remain yet been used.

Arthur – With only one exception, the name has been associated with only a tropical storm. The 1984 edition was a weak tropical storm east of the Lesser Antilles. The 1990 version was stronger and crossed into the Caribbean. In 1996, the storm named Arthur made landfall in North Carolina before curving back to sea. In 2002, the cyclone formed east of North Carolina and headed to Newfoundland. The 2008 version formed from the remnants of Pacific Tropical Storm Alma (and made landfall in Belize. In 2014, there was finally a Hurricane Arthur. It made landfall in North Carolina on July 4. 2020’s Arthur developed over the Gulf Stream and made a close brush with the Outer Banks.

Bertha – For Americans, this might be the most notorious name on the list. While the 1984 edition was a weak tropical storm at sea, 1990‘s Bertha was a category one hurricane that made landfall in Nova Scotia. In 1996, it was a major hurricane that made landfall in North Carolina as a category one (Particularly memorable for me as my father and I drove around the periphery of it post-landfall as we traveled from Tallahassee to Chesapeake, VA. A downed limb on US 17, east of the Great Dismal Swamp, caused a tire blow-out and quite the soaking for us when we changed the tire in the dark.) 2002‘s Bertha was a weak tropical storm that made landfall in southeast Louisiana while the 2008 iteration was the longest-lived and eastern-most forming July tropical cyclone on record. 2014‘s Hurricane Bertha was more forgettable (though in extratropical life, the storm did have a substantial effect on Europe). 2020 Bertha will be remembered for its quick and rather unexpected formation. At 12:50 AM on May 27, the Tropical Weather Outlook projected a 30% chance of tropical cyclone formation and that probability went up to 70% with a 7:25 AM forecast. The National Hurricane Center initiated advisories just over an hour later for the one day storm.

Cristobal – Replaced Cesar after 1996. The 2002 edition was a weak tropical storm at sea, while 2008‘s formed east of North Carolina and traveled northeast. In 2014, Cristobal produced heavy rains over some Caribbean islands but was otherwise un-notable.

Dolly – Replaced Diana after 1990. The inaugural edition made landfall in Mexico as a category 1 hurricane in 1996. In 2002, it was a tropical storm at sea, while in 2008 it was a landfalling hurricane once again; this time on the Yucatan Peninsula and south Texas. The 2014 version was a short-lived Bay of Campeche storm.

Edouard – In 1984, the storm had a quick life and death in the Bay of Campeche. In 1990, it was a tropical storm that meandered around the Azores. It was the strongest hurricane (category four) of the 1996 season and threatened New England before curving away. The 2002 edition made landfall in Ormond Beach, Florida as a tropical storm while 2008‘s struck Texas. The 2014 version remained at sea but marked the first time NOAA used unmanned aircraft systems to collect data in a hurriane.

Fay – Replaced Fran after 1996. The tropical storm of 2002 hit near Matagorda, Texas. In 2008, the storm crossed over Hispanola and Cuba before making four landfalls in Florida (at Key West, Naples, Flagler Beach, and Carabelle). The 2014 hurricane made landfall on Bermuda at category one strength.

Gonzalo – Made its debut in October of 2014 and affected a number of the Leeward Islands as well as Bermuda, where it made landfall just six days after Fay.

Hanna – Replaced Hortense after 1996. In 2002, it was a tropical storm with landfalls at the mouth of the Mississippi River and the Alabama/Mississippi border. The 2008 hurricane made landfall near the North Carolina/South Carolina border and worsened flooding in Haiti, which had already been affected by Fay and Gustav. Were it not for the latter, the name Hanna likely would have been retired. The 2014 version was a strange affair. The preceding tropical depression formed out of the remnants of Pacific Tropical Storm Trudy in the Bay of Campeche and travelled east. It degenerated to a remnant low before coming back to life east of the Nicaragua/Honduras border and became a tropical storm just before making landfall in Nicaragua.

Isaias – This name was added to the list after the 2008 season to replace Ike, which had replaced Isidore after 2002. It was not used in the 2014 season so it still has has a chance to join Igor and Irma on the list of ‘I’ storms that were retired after just one appearance.

Josephine – In 1984, it was a category two hurricane at sea, while 1990‘s was a category one. The 1996 tropical storm tracked east across the Gulf of Mexico and made landfall in an uninhabited part of Taylor County, Florida. The 2002 and 2008 versions were tropical storms at sea (though remnants of the latter did bring flooding to St Croix).

Kyle – Replaced Klaus after 1990. In 1996, it was a short-lived tropical storm off the coast of Central America. In 2002, it was a wayward hurricane that ultimately hit the Carolinas while curving to the northeast and subsequently absorbed by a cold front. The 2008 edition was also a hurricane and made landfall near Yarmouth, Nova Scotia.

Laura – Replaced Lili after 2002. It was a north Atlantic tropical storm in 2008.

Marco – It was the only tropical cyclone to make landfall in the United States (near Cedar Key, Florida) in 1990. It was a wayward hurricane in the Caribbean Sea in 1996. The 2008 version was a small tropical storm in the Bay of Campeche.

Nana – 1990 marked the first time that a storm name starting with the letter N made an appearance; it was a hurricane at sea. The 2008 version was a short-lived tropical storm at sea.

Omar – In 2008, it was a category four hurricane, which formed in the Caribbean Sea and moved to the northeast before eventually dissipating west of the Azores.

Paulette – Replaced Paloma after the 2008 season.

Rene, Sally, Teddy, Vicky, and Wilfred have never been used. If the higher-end of some of the season forecasts are correct, we will see (at least) some of them for the first time in 2020.

2019 Atlantic Storm Names

June 1, 2019

Here we are on June 1st, at the start of another hurricane season in the Atlantic. Per my (admittedly not quite reliable) tradition, here is my review of the storm names for the season. Where did these unfamiliar names come from? What happened to some of the familiar ones? The answers come out below.

This year’s list of names is the seventh iteration of the list first used in 1983. This list has had the most changes (total of 13) along with the most names retired from the original group (10). Owing to the low number of storms in 1983, there are only two names that have been used in each iteration . Three of the names have never been used and one is on the list for the first time. The names (with links for years to images of the tracking chart for the storm and links for retired names to the Wikipedia entry):

Andrea – This spot on the list was originally filled by Alicia, which was replaced by Allison in 1989. Allison was the first tropical storm to have its name retired. Andrea debuted in 2007 as a pre-season subtropical storm off the southeastern United States. The 2013 edition made landfall as a tropical storm in the Big Bend of Florida. This year, it was a sub-tropical storm south of Bermuda that had a short existence.

Barry – In 1983, a category 1 hurricane that had made landfall (as a tropical depression) at Melbourne, Florida before trans-versing the Gulf of Mexico to make landfall in northern Mexico. Tropical storm at sea in 1989. Hit Nova Scotia as a tropical storm in 1995. In 2001, made landfall on the Florida panhandle, again as a tropical storm. The 2007 edition also paid a visit to Florida as a tropical storm before traveling up the east coast in a post-tropical life. In 2013, the tropical storm made landfall in Mexico from the Bay of Campeche

Chantal – Category 1 hurricane at sea in 1983. The 1989 version struck Texas and was responsible for 13 fatalities (all due to drowning, the sad details can be read here). Tropical storm at sea in 1995 and in the Caribbean in 2001. The 2007 edition was a short-lived tropical storm that caused flooding in Newfoundland in its post-tropical life. In 2013, the tropical storm made landfall in Hispaniola.

Dorian – Debuted in 2013 as the replacement for the monster of the 2007 season, Dean.

It was a much less notable storm, which had a difficult life at sea.

Erin – Category 2 hurricane at sea in 1989. Made landfall near Vero Beach, Florida as a category one hurricane , crossed the peninsula and made a second landfall near Fort Walton Beach as a category 2 in 1995. In 2001 it was an “interrupted-track” storm that eventually became a category three hurricane and passed just east of Bermuda and later Cape Race, Newfoundland (in its final hours as a tropical storm). The 2007 edition struck Texas as a tropical storm and the remnant low persisted into Oklahoma and strengthened briefly; the storm report has a paragraph on why the NHC did not consider it to be a tropical cyclone over Oklahoma despite its convective organization and relatively high winds. The 2013 version was a tropical storm at sea.

Fernand – In 2013, it was a tropical storm that caused 14 deaths in and around Veracruz, Mexico. It replaced the name of the other category 5 hurricane of 2007, Felix.

Gabrielle – Category 4 hurricane at sea in 1989. Small tropical storm into northern Mexico in 1995. The 2001 edition caused a fair bit of flooding in Florida after making landfall on the west coast near Venice before re-intensifying to a category 1 hurricane in the Atlantic. In 2007, the name was attached to a short-lived tropical storm that affected the Outer Banks of North Carolina. The 2013 version was also short-lived.

Humberto – Added to the list in 1995, replacing Hugo. The debut edition was a Category 2 hurricane as was the subsequent 2001 storm. In 2007, it formed from the remnants of the same front that spawned Gabrielle. It went from tropical depression to hurricane in less than 19 hours and was rapidly strengthening prior to landfall at High Island, Texas.

The 2013 version was one of only two hurricanes that season. It affected the Cape Verde Islands as a tropical storm.

Imelda– New for 2019, replacing Ingrid, which had replaced Iris after the 2001 season.

Jerry – Hit upper Texas as a category 1 hurricane in 1989. The 1995 version affected central Florida as a tropical storm. 2001 and 2007 editions were fairly short-lived tropical storms. The 2013 version was not particularly notable, either.

Karen – Loopy tropical storm in the western Caribbean in 1989. Tropical storm at sea in 1995. Was a category 1 hurricane in 2001 before making landfall in the Canadian maritimes as a tropical storm. The 2007 version was briefly a hurricane in the mid-Atlantic. In 2013, it was a rare tropical storm to form in the Gulf of Mexico but dissipate before landfall.

Lorenzo – Replaced 1995’s Luis. Tropical storm in 2001. Quick forming category 1 hurricane that struck Veracruz, Mexico in 2007. Like so many other storms in 2013, it was not particularly memorable.

Melissa – Replaced 2001’s Michelle, which was a one time replacement for Marilyn. Was a short-lived tropical storm just west of the Cape Verde Islands in 2007 and also was not around long in 2013

Nestor – The name was added to the list for the 2013 season to replace Noel, a category1 hurricane that was directly responsible for no fewer than 163 deaths at the end of October 2007. It has not yet been used.

Olga – Replaced 1995’s Opal. A wayward category 1 hurricane at sea in 2001. Made an east-west crossing of Hispaniola as a tropical storm in post-season 2007, causing 40 deaths along the way.

Pablo – Only appearance was in 1995 as a weak tropical storm.

Rebekah – Replaced Roxanne in 1995, but is yet to debut.

Sebastian – Tropical storm in 1995 that hit the island of Anguilla before dissipating in the Caribbean.

Tanya – Was a category 1 hurricane in 1995 before striking the Azores as a tropical storm. It was the first time that a name starting with the letter T had been used.

Van – Never used.

Wendy – Never used.

2018 Atlantic Storm Names

June 1, 2018

It’s the first day of the hurricane season, which means the Tropical Weather Outlooks issued by the National Hurricane Center today contain the names that will be used this season along with their pronunciations. Here are my notes on where you may have heard a name before and which names have never been used before.

This set of names was first used in 1982. That season is rather famous for its inactivity. A few subsequent seasons that used this set of names were also relatively quiet. Because of that, only four of the original names have been retired, which makes this the list the least changed.

Alberto al-BAIR-toe – In 1982 he managed to go from nothing to hurricane and back to nothing in the short space between the Yucatan Peninsula and the coast of West Florida. Tropical storm in 1988 and 1994. Central Atlantic category 3 in 2000. 2006 edition came ashore in Florida as a tropical storm. Short-lived tropical storm in 2012. 2018’s Alberto was a sub-stropical storm that remained a trackable entity far, far, inland.

2018’s Alberto

Beryl BEHR-ril – All six times were as a tropical storm (1982, 1988, 1994, 2000, 2006). 2012 version made landfall in Jacksonville Beach, FL and was the strongest landfalling May tropical cyclone since the May 29, 1908 hurricane.

Chris kris – Tropical storm in 1982 , 1988, and 2000. Hurricane at sea in 1994. 2006 tropical storm affected the Bahamas and Greater Antilles before abruptly dissipating. It was a category 1 hurricane at sea in 2012.

Debby DEH-bee – Category four hurricane at sea in 1982. Bay of Campeche hurricane in 1988. Tropical Storm in 1994. Leeward Islands hurricane in 2000. Tropical storm at sea in 2006. In 2012, it was a tropical storm that caused flooding in the Big Bend region of Florida.

Ernesto er-NES-toh – Until 2006, always a tropical storm and never a hurricane (1982, 1988, 1994, 2000). 2006 hurricane made first landfall near Guanatamo Bay, Cuba, weakend to a tropical storm and made subsequent landfalls in Dade County, Florida and Oak Island, North Carolina. Hit the Yucatan Peninsula as a category two hurricane in 2012.

Florence FLOOR-ence – Gulf of Mexico hurricane in 1988 (passed directly over New Orleans at tropical storm strength). At sea hurricane in 1994 and 2000 and 2006; latest of those affected Bermuda and Newfoundland. In 2012, it was a tropical storm in the east Atlantic.

Gordon GOR-duhn – This spot was held by Gilbert until after the 1988 season. In 1994 a hurricane with a wacky course (at TS strength) through the Caribbean Sea and Straits of Florida en route to briefly threaten the Outer Banks before turning back south. In 2000, the hurricane took a straight line course from the Yucatan to the Big Bend of Florida. 2006 ‘s version was a major hurricane at sea. The 2012 edition was a hurricane that affected the Azores.

Helene heh-LEEN – Category four at sea in 1988 and a tropical storm in 2000. Like Gordon, a major hurricane at sea in 2006. In 2012, a tropical depression formed in the deep tropics only to subsequently degenerate to a tropical wave before it crossed into the Caribbean. The remnants eventually reached the Bay of Campeche where they became Tropical Storm Helene.

Isaac EYE-zik – Tropical storm in 1988, category four at sea in 2000. A catagory one hurricane that weakened before brushing Nova Scotia in 2006. Last name to be used that year. In 2012, Isaac was a category one hurricane that made landfall in Louisiana and was directly responsible for 34 deaths. most of which were due to flooding in Haiti.

Joyce joyss– This spot was held by Joan until after the 1988 season. Joyce debuted in 2000 as a hurricane that weakened before crossing into the Carribean. The 2012 version was a tropical storm in the deep tropics.

Kirk kurk – Added to the list in 2006, taking the spot held by Keith. Debuted in 2012 as a category two hurricane at sea.

Leslie LEHZ-lee – A tropical storm in 2000. In 2012, a category one hurricane that affected the Canadian maritimes as an extratropical storm.

Michael MY-kuhl – Hurricane in 2000. Hit Newfoundland as an extratropical system. 2012 hurricane made a couple of u-turns in the mid-Atlantic.

Nadine nay-DEEN – Tropical storm in 2000. The 2012 hurricane was not impressed by MIchael’s turning ability.

Hold my beer, Michael

Oscar AHS-kur – Quiet 2012 as a short lived mid-ocean tropical storm.

Patty PAT-ee – Also a forgettable 2012 tropical storm.

Rafael rah-fah-ELL – 2012 hurricane that caused flooding in the Caribbean and also brought heavy swells to the coast of Nova Scotia.

Sara SAIR-uh – Knee deep in the hoopla, this is the replacement name for Sandy

Tony TOH-nee – 2012 tropical storm in the deep Atlantic.

Valerie VAH-lur-ee and William WILL-yum have never been used. The various hurricane season forecasts suggests that we are not likely to see either of those names or many of the names that we saw in 2012. As hurricanes Gilbert and Joan showed in 1988, however, a low number of storms is no guarantee of a lack of exceptionally destructive storms.

2014 Atlantic Storm Names

June 2, 2014

Yesterday marked the first day of the Atlantic Hurricane Season and per custom, the National Hurricane Center posted their first Tropical Weather Outlook with the list of names that will be used this season along with their pronunciations. It has been my custom to provide a history of these names to suggest why a name may sound familiar and to show where the unfamiliar names came from.

This year’s list was first used in 1984. Nine original names have been retired, which is the second-most retired from the six lists. As is the case for half of the lists, the name beginning with the letter I has been replaced twice. There are five names original to the list which have not yet been used and three are new for 2014.

Arthur – Each time this name was used, it was in association with a tropical storm that did not become a hurricane. The 1984 edition was a weak tropical storm east of the Lesser Antilles. The 1990 version was stronger and crossed into the Caribbean. In 1996, the storm named Arthur made landfall in North Carolina before curving back to sea. In 2002, the cyclone formed east of North Carolina and headed to Newfoundland. The 2008 version formed from the remnants of Pacific Tropical Storm Arthur (a scenario which is in play at this moment in 2014) and made landfall in Belize.

Bertha – For Americans, this might be the most notorious name on the list. While the 1984 edition was a weak tropical storm at sea, 1990‘s Bertha was a category one hurricane that made landfall in Nova Scotia. In 1996, it was a major hurricane that made landfall in North Carolina as a category one (Particularly memorable for me as my father and I drove around the periphery of it post-landfall as we traveled from Tallahassee to Chesapeake, VA. A downed limb on US 17, east of the Great Dismal Swamp, caused a tire blow-out and quite the soaking for us when we changed the tire in the dark.) 2002‘s Bertha was a weak tropical storm that made landfall in southeast Louisiana while the 2008 iteration was the longest-lived and eastern-most forming July tropical cyclone on record.

Cristobal – Replaced Cesar after 1996. The 2002 edition was a weak tropical storm at sea, while 2008‘s formed east of North Carolina and traveled northeast.

Dolly – Replaced Diana after 1990. The inaugural edition made landfall in Mexico as a category 1 hurricane in 1996. In 2002, it was a tropical storm at sea, while in 2008 it was a landfalling hurricane once again; this time on the Yucatan Peninsula and south Texas.

Edouard – In 1984, the storm had a quick life and death in the Bay of Campeche. In 1990, it was a tropical storm that meandered around the Azores. It was the strongest hurricane (category four) of the 1996 season and threatened New England before curving away. The 2002 edition made landfall in Ormond Beach, Florida as a tropical storm while 2008‘s struck Texas.

Fay – Replaced Fran after 1996. Both editions since have been landfalling tropical storms. 2002‘s hit near Matagorda, Texas. In 2008, the storm crossed over Hispanola and Cuba before making four landfalls in Florida (at Key West, Naples, Flagler Beach, and Carabelle).

Gonzalo – We finally reach one of the new names. It is the replacement for Gustav.

Hanna – Replaced Hortense after 1996. In 2002, it was a tropical storm with landfalls at the mouth of the Mississippi River and the Alabama/Mississippi border. The 2008 hurricane made landfall near the North Carolina/South Carolina border and worsened flooding in Haiti, which had already been affected by Fay and Gustav. Were it not for the latter, the name Hanna likely would have been retired.

Isaias – New for 2014, this name replaces Ike, which replaced Isidore after 2002.

Josephine – It is pretty unusual to have a name this deep in the list that is both original and has been used every time, but here we are. In 1984, it was a category two hurricane at sea, while 1990‘s was a category one. The 1996 tropical storm tracked east across the Gulf of Mexico and made landfall in an uninhabited part of Taylor County, Florida. The 2002 and 2008 versions were tropical storms at sea (though remnants of the latter did bring flooding to St Croix).

Kyle – Replaced Klaus after 1990. In 1996, it was a short-lived tropical storm off the coast of Central America. In 2002, it was a wayward hurricane that ultimately hit the Carolinas while curving to the northeast and subsequently absorbed by a cold front. The 2008 edition was also a hurricane and made landfall near Yarmouth, Nova Scotia.

Laura – Replaced Lili after 2002. It was a north Atlantic tropical storm in 2008.

Marco – It was the only tropical cyclone to make landfall in the United States (near Cedar Key, Florida) in 1990. It was a wayward hurricane in the Caribbean Sea in 1996. The 2008 version was a small tropical storm in the Bay of Campeche.

Nana – 1990 marked the first time that a storm name starting with the letter N made an appearance; it was a hurricane at sea. The 2008 version was a short-lived tropical storm at sea.

Omar – In 2008, it was a category four hurricane, which formed in the Caribbean Sea and moved to the northeast before eventually dissipating west of the Azores.

Paulette – New for 2014, this name is the replacement for Paloma.

Rene, Sally, Teddy, Vicky, and Wilfred have never been used. If the hurricane season forecasts are accurate, they will have to wait until 2020 to possibly make an appearance.

At the turn of the hurricane season

August 25, 2013

The Atlantic hurricane season has been, by the reckoning of most, been very quiet. This feeling is to some extent exacerbated by the unanimous predictions of above average activity that preceded the season’s start. Some people may argue against this notion by pointing out that having four named storms in the book before the end of August connotates a season that is anything but quiet; indeed that was significantly ahead of the climatological norm. However, in terms of aggregate activity, the Atlantic basin has been rather exceptionally lacking in activity. Interestingly, by similar measures so its western hemisphere counterpart has not been notably active, either. The tranquility in the Atlantic is set to end soon.

While there have been five tropical storms in the Atlantic so far this year, none have sustained that status for more than three days or have come very close to being a hurricane. As such, they don’t add up to much in terms of aggregate activity. One measure of this is Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE). It is calculated by squaring the maximum wind speed of a tropical storm/hurricane at the six hour “synoptic time” intervals. The number is made manageable by dividing by 10,000 and while the resulting unit is technically knots2,, the reduced number is referred to simply as a unit of ACE. To understand the numbers, it is helpful to remember that a 50 knot tropical storm persisting for one day generates 1 unit of ACE while a major hurricane with maximum wind speed of 100 knots generates 1 unit of ACE every six hours, 4 units per day.

As I write this, the Atlantic hurricane season only has roughly 7.6 units of ACE to its name. The year-to-date normal is 23 units. Again, the short-lived nature of the tropical storms not to mention the absence of hurricanes, let alone major ones, is to account for this. Having such a low sum this deep into the season is not without precedent, even during the post-1994 active period. At this point in 2002, the season just had 3 units in the books and 2001 had just fewer than 9. Such low figures were more normal in the 1981-1994 time-frame; as 1984 did not see a tropical storm until August 29, it had 0 units at this time.

Often times, a lack of activity in the Atlantic is off-set by high activity in the Pacific. Such was the case in 1984 when five major hurricanes had formed in the eastern Pacific before the calendar turned to September; 71 units of ACE to its credit going into the final week of August. During the active period of the Atlantic basin, such inequities exist during the El Niño Seasonal Oscillation, which tends to suppress tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic while enhancing that of the Pacific. Some times the El Niño is readily apparent in the amount of eastern Pacific activity, as was the case in 2006, when the first ever (and to date, only) Central Pacific category 5 hurricane, Ioke, helped contribute to a whopping 90 units of ACE being tallied before the final week of August.

2013 does not fit into that paradigm, however. Rather than El Niño, we have what some jokingly call “La Nada”, the oscillation is in a neutral state that does not favor either the west Atlantic or easter Pacific basin. Furthermore, while the eastern Pacific has featured six hurricanes so far, none have became major hurricanes. It is the furthest we have gone into the season without a major hurricane in the western hemispher since 2003 when Fabian, the third hurricane of that season, attained major status on August 30th. Going back to the beginning of reliable records for the eastern Pacific basin, the latest date for the first major hurricane in either basin is September 7th (Floyd, 1981). Combined the two basins have accounted for 53 units of ACE, the fifth lowest total since 1980.

Using that season to date figure to try to predict the future is no straight-forward; wide variations in the spacing of activity make many seasons “front-loaded” or “back-loaded” with activity relative to the present. Also, there is a wide range of variation across the seasonal sums of ACE for both basins. There is no “magic number” that is guaranteed to be the total for any given season. While the two basins tend to compensate for each other and have a stable average total over the long term, that relationship is only clear over the long term. I will, however, proceed cautiously in presenting those seasons with comparably low levels of activity in both basins to give a sense of what may be expected for the rest of the season:

| Season | Atlantic ACE pre Aug 25 |

Pacific ACE pre Aug 25 |

Combined pre August 25 |

Atlantic total for season |

| 2001 | 8.89 | 29.1625 | 38.025 | 106 |

| 2003 | 20.485 | 18.245 | 38.73 | 175 |

| 2002 | 3.345 | 41.66 | 45.005 | 67 |

| 1981 | 9.9625 | 37.1975 | 47.16 | 93 |

| 2013 | 7.6525 | 45.81 | 53.4625 | ??? |

Despite the average-below average starts to these four seasons, the only to finish distinctly below-average in terms of ACE was 2002, a season in which moderate El Niño conditions were present.** 1981 is a perfect fit for NOAA’s definition of a season with average activity (but was a busy season by 1980’s standards). 2003 had three hurricanes at this point, but three major hurricanes were yet to come. The director of the National Hurricane Center, Rick Knabb, tweeted about the 2001 hurricane season a few days ago. The first hurricane, Erin, did not arrive until September 9th but the season ended with four major hurricanes in the ledger.

I suspect 2013 will bear resemblance to 2001. Doing so would put the season in line with the pre-season predictions for storm numbers, albeit with a bit lower ACE than anticipated. While we had a bit of a false alarm a bit over a week ago ***, it appears that the turn of the season is upon us and activity is about to pick up substantially. Forecast models are indicating that a tropical wave currently exiting Africa may become a tropical cyclone in five to six days time in the deep tropical Atlantic, approximately 1000 miles east of the Lesser Antilles. This afternoon’s Tropical Weather Outlook from the National Hurricane Center gives the wave a 20% chance of becoming a tropical cyclone in the next five days. Given the time of year, such a system would have to monitored closely due its relative close-in development. Furthermore, the GFS model is currently showing development of the subsequent wave as well.

If one had to summarize the reason for the quiet season to date in one graphic, it would be hard to do better than this:

The graphic comes from NOAA’s Tropical Cyclone Formation Probability product. As vertical instability is a necessary component of formation and maintenance of tropical cyclones, it is one of the key data inputs for the product. As the graphic shows, instability in the tropical Atlantic has been below normal for the entirety of the season. Its relative absence has been a key factor in the shortened lives of Tropical Storms Dorian and Erin as well as the lack of additional tropical cyclone formation. While it has not yet reached a climatologically normal level, it is as high as it’s been all season.

The graphic comes from NOAA’s Tropical Cyclone Formation Probability product. As vertical instability is a necessary component of formation and maintenance of tropical cyclones, it is one of the key data inputs for the product. As the graphic shows, instability in the tropical Atlantic has been below normal for the entirety of the season. Its relative absence has been a key factor in the shortened lives of Tropical Storms Dorian and Erin as well as the lack of additional tropical cyclone formation. While it has not yet reached a climatologically normal level, it is as high as it’s been all season.

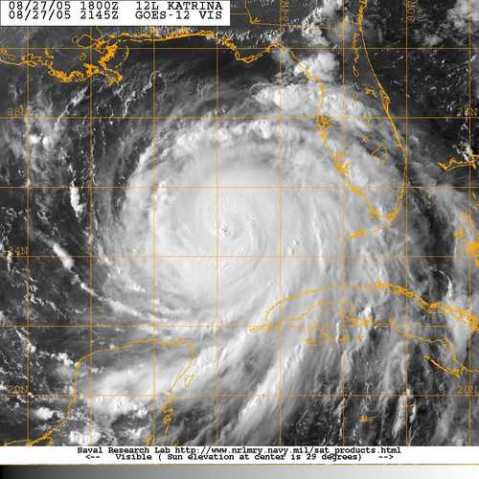

While I have been composing this post, the sixth tropical cyclone of the season has formed in the Bay of Campeche. A WC-130 is en-route to determine whether it is a tropical storm. I cannot help but be reminded of what I call the “phony season” part of the 2005 hurricane season. From mid-July to mid-August there was a succession of insignificant storms, which mostly struggled in hostile conditions in the tropical Atlantic. The last of those was the tropical cyclone that seemed poised for development, Tropical Depression Ten. About a week later, a tropical storm, Jose. similar to our newly formed Tropical Depression Six, formed in the Bay of Campeche and the real season was back with a vengeance****. Hostile conditions do not last forever.

Will we have our first major hurricane landfall since Wilma in that season without equal? Will we see our first category five hurricane since Felix, nearly six years ago? Those are questions for which we will have to wait for the answers. While we are free to hope that the balance of the season passes without incident, such an occurrence is not probable. We must be prepared.

** Mind you, below-average ACE does not necessarily equate to a quiet season as victims of Hurricanes Isidore and Lili will attest.

*** See, for example, the Colorado State University forecast team’s prediction for tropical cyclone activity from August 16 to August 29. Anticipating development of Invests 92 and 94 as well as Erin being longer-lived, the forecast called for above average levels of ACE for the two week forecast period. That forecast will go down as big bust.

**** Jose, of course, is the name that Tropical Depression Ten would have received had it become a tropical storm. And there was a time when it appeared the remnant bits, future Tropical Depression Twelve / Katrina, would get that name. Great example of the hazard of bandying about a name for a disturbance or tropical depression before the name is actually earned.

A perhaps under-appreciated bit of progress made in computer modeling with regards to tropical cyclones is how accurate they’ve become in forecasting development of some types of disturbances well in advance. Over the past decade, dynamic models have forecast tropical cyclogenesis farther in the future, sometimes before the spawning disturbance is even in the Atlantic Ocean, and crucially, with fewer false positives. Tomorrow, the National Hurricane Center will avail itself in these advances when they release their first Tropical Weather Outlook that covers a five-day period. For the first time, the NHC’s four-times a day guidance on which disturbances are being monitored for potential tropical cyclone development will extend beyond 48 hours. It is a part of an evolution that’s been ongoing for just over a decade. The evolution has given greater clarity to the Hurricane Center’s thoughts on the probability of development.

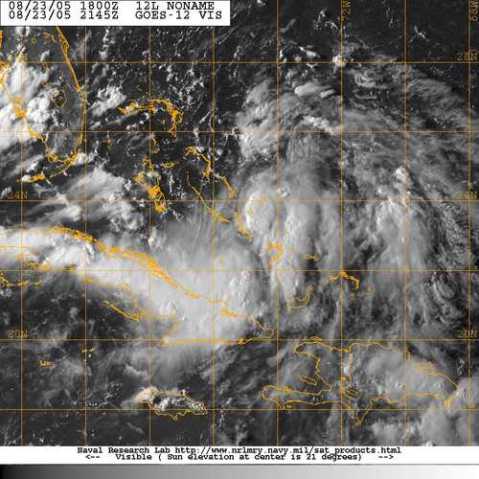

Let us remind ourselves of the form that the Tropical Weather Outlook had for most of the decades of its existence. The following paragraphs are taken from the nominal 5 PM Outlook on Monday, August 22, 2005 and the forecaster was future NHC director Rick Knabb:

A LARGE TROPICAL WAVE IS LOCATED OVER THE EASTERN ATLANTIC OCEAN

ABOUT 525 MILES WEST OF THE CAPE VERDE ISLANDS. THE ASSOCIATED

SHOWER ACTIVITY REMAINS LIMITED… BUT THIS SYSTEM HAS SOME

POTENTIAL FOR SLOW DEVELOPMENT DURING THE NEXT DAY OR TWO AS

IT MOVES WESTWARD OR WEST-NORTHWESTWARD AT 10 TO 15 MPH.DISORGANIZED CLOUDINESS AND SHOWERS EXTEND FROM EASTERN CUBA AND

HISPANIOLA ACROSS THE SOUTHEASTERN BAHAMAS AND THE TURKS AND CAICOS

ISLANDS… AND INTO THE ATLANTIC FOR SEVERAL HUNDRED MILES. THIS

ACTIVITY IS POSSIBLY ASSOCIATED WITH THE REMNANTS OF TROPICAL

DEPRESSION TEN… AND DEVELOPMENT DURING THE NEXT DAY OR TWO SHOULD

BE SLOW TO OCCUR AS THE SYSTEM MOVES WESTWARD OR WEST-

NORTHWESTWARD.ELSEWHERE… TROPICAL STORM FORMATION IS NOT EXPECTED THROUGH

TUESDAY.

In this format, the outlooks made an effort to communicate what the forecaster’s thoughts were on the potential for development. Admittedly though, the wording could be “fuzzy” at times, and it required a close reading on a 6 hour basis to sniff out changes in wording that may have indicated the forecaster thinking more highly of the system’s future prospects. We’ll continue with the system mentioned in the third paragraph as an example on how the wording would change as development occurred:

CLOUDINESS AND SHOWERS EXTEND FROM EASTERN CUBA AND HISPANIOLA

ACROSS THE SOUTHEASTERN BAHAMAS AND THE TURKS AND CAICOS ISLANDS…

AND INTO THE ATLANTIC FOR A FEW HUNDRED MILES. THIS ACTIVITY IS

POSSIBLY ASSOCIATED WITH THE REMNANTS OF TROPICAL DEPRESSION TEN.

GRADUAL DEVELOPMENT OF THIS SYSTEM IS POSSIBLE DURING THE NEXT DAY

OR TWO AS IT MOVES WEST-NORTHWESTWARD AT ABOUT 10 MPH.

So, we’ve gone from “development should be slow to occur” to “gradual development is possible”. This is an example of a subtle change where it would be hard for the average person to discern whether this was merely re-wording or a slight change in thinking.

CLOUDINESS AND SHOWERS EXTEND FROM EASTERN CUBA AND HISPANIOLA

ACROSS THE SOUTHEASTERN BAHAMAS AND THE TURKS AND CAICOS ISLANDS…

AND INTO THE ATLANTIC FOR A FEW HUNDRED MILES. THIS ACTIVITY…

WHICH IS POSSIBLY ASSOCIATED WITH THE REMNANTS OF TROPICAL

DEPRESSION TEN…HAS BECOME MORE CONCENTRATED THIS MORNING NEAR THE

SOUTHEASTERN BAHAMAS. ADDITIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF THIS SYSTEM IS

POSSIBLE DURING THE NEXT DAY OR TWO AS IT MOVES WEST-NORTHWESTWARD

AT ABOUT 10 MPH. AN AIR FORCE RESERVE HURRICANE HUNTER AIRCRAFT IS

SCHEDULED TO INVESTIGATE THE SYSTEM THIS AFTERNOON…IF NECESSARY

Now, “additional development is possible”. Certainly an upgrade based on existing circumstances. Seems like we’re getting closer to something happening, but how close?

A BROAD SURFACE LOW PRESSURE AREA IS PRODUCING WIDESPREAD CLOUDINESS

AND THUNDERSTORMS FROM EASTERN CUBA AND HISPANIOLA NORTHWARD ACROSS

THE SOUTHEASTERN BAHAMAS…THE TURKS AND CAICOS ISLANDS… AND INTO

THE ATLANTIC FOR A FEW HUNDRED MILES. THIS ACTIVITY HAS BECOME A

LITTLE BETTER ORGANIZED OVER THE SOUTHEASTERN BAHAMAS… AND A

TROPICAL DEPRESSION COULD FORM LATER TODAY OR ON WEDNESDAY AS THE

SYSTEM MOVES TO THE WEST-NORTHWEST OR NORTHWEST AT 5 TO 10 MPH. AN

AIR FORCE RESERVE UNIT RECONNAISSANCE AIRCRAFT IS SCHEDULED TO

INVESTIGATE THE SYSTEM THIS AFTERNOON. INTERESTS IN THE BAHAMAS…

THE NORTH COAST OF CUBA…AND SOUTHERN FLORIDA SHOULD MONITOR THE

PROGRESS OF THIS SYSTEM.

Now it’s clear that we’re real close. No ambiguity in “a tropical depression could form later today…” And that was indeed the case

THE NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER HAS INITIATED ADVISORIES ON TROPICAL

DEPRESSION TWELVE… LOCATED OVER THE CENTRAL BAHAMAS ABOUT 175

MILES SOUTHEAST OF NASSAU.

(For those wondering about the fate of the other disturbance mentioned in the first Outlook from which I quoted, it would go on to be mentioned in Outlooks for the entire lifespan of Katrina, with the last mention coming almost exactly a week later stating that associated shower activity had diminished. It ran nearly the entire gamut of phrasing.)

The Outlooks quoted above were part of a study conducted to assess the feasibility of incorporating categorical probability (low, medium, high chance) of development into the Tropical Weather Outlook. As detailed in a paper presented at the American Meteorological Society’s 2008 Hurricane Conference, “Verification of the National Hurricane Center’s Experimental Probabilistic Tropical Cyclone Genesis Forecasts“, the study showed potential for the idea and it was tested in-house during the 2007 season, (which happened to be the first year of the Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook, then in experimental form). The testing demonstrated that the idea would work and it was subsequently incorporated into the 2008 Outlooks and continued their form in 2009.

Over time. in-house forecasting using explicit 10% increments (rather than low, medium, and high categories) showed enough refinement that the 2010 Outlooks used the percentages. As explained in the 2010 season verification report (section four), forecasts were well calibrated for the high and low end percentages, but there was an inversion in the middle range (a greater percentage of systems with a 40% chance of development actually developed than those with a 70% chance). The summary of 2007-2010 forecasts reflected some of that calibration issue, but overall the forecasts matched up well.

So, the forecasters were making progress with the product they had in its current scope, but it was becoming clear that potential existed to broaden that scope. Hurricane Julia of 2010 provided an example of forecast models providing accurate guidance outside of the bounds of the Tropical Weather Outlook;

So, the forecasters were making progress with the product they had in its current scope, but it was becoming clear that potential existed to broaden that scope. Hurricane Julia of 2010 provided an example of forecast models providing accurate guidance outside of the bounds of the Tropical Weather Outlook;

The genesis of Julia was not well anticipated. The disturbance that became Julia was introduced into the Tropical Weather Outlook (TWO) with a medium (30%) chance of formation

only 18 h before the system became a tropical cyclone. This prediction was raised to a high (70%) chance 6 h before genesis occurred. The lateness in mentioning the disturbance that spawned Julia may have been due to the typical operational practice of not introducing an African wave disturbance into the TWO until it reaches the Atlantic Ocean. In this case, the disturbance developed into a tropical cyclone only about one day after leaving the West African coast. It is of note that many of the global model forecasts successfully called for the genesis of Julia up to several days in advance.

(Discovery of a Master’s thesis on the genesis of Hurricane Julia helped provide this example.)

Julia was not a solitary case. While there were certainly instances of “quick-draw” development not foreseen by the models, they were proving to be adept at the “classical” mode of development, the Cape Verde storm. The NHC was aware of this and had started performance of 5-day Outlooks that were kept in house and results were reported at the 2012 AMS Hurricane Conference (“Extended-range genesis forecasts at the National Hurricane Center” recorded presentation). The results start being shown about five minutes into the presentation and the presenter, NHC hurricane specialist Eric Blake explained that one issue they saw with the extended part of the forecasts (days 3-5) was that many systems that were given a mid-range probability of developing during that time period actually developed earlier (in the 1-2 day timeframe). 25% of systems in that 40%-60% range failed to ever develop. However, they were all systems that would go on to be in the short-range outlook; they weren’t phantom systems. Once upon a time, the prevalence of “boguscanes” in the models was such that this would have been a difficult feat to achieve.

The presentation went on to show the results for the eastern Pacific basin, interestingly, even though forecasters were aware of their tendency to under-estimate the probability of development (and Blake said that he had started to take that tendency into consideration and adjusting his forecasts accordingly) there was still an under-forecasting bias in that basin. At the 9:45 mark he shows a comparison of the short-term and extended term forecasts for each storm in the 2010 season. One sees that the in-house Outlooks containing Julia picked up on the potential for development four days in advance and that Lisa was another storm seen well in advance.

The work continued and before this season began, the NHC had announced that 5 day Outlooks would become public at some point in this season. A presentation of the 5 day outlooks was made at the 2013 National Hurricane Conference. The outlooks will give the usual write-up and 0-48 hour percentage chance of development for existing systems and have a separate section for systems that exist/are only in the extended time-frame and have a near 0% chance of developing in the short term. Blake’s presentation touched on some of the issues with a graphical presentation (e.g. how to handle systems that overlap) and it appears those have not been fully resolved yet; the announcement of the August 1 debut of the extended Tropical Weather Outlook states that the accompanying graphic is under development and “may become available later this season”.

This new product represents a great deal of progress that has been made in forecasting tropical cyclogenesis. A great deal remains, however. Two customers that expressed interest in these extended outlooks, the oil services industry and the US Navy, might be disappointed, in the near term, at least. While the models have shown increased skill in anticipating storms in the deep tropics, the Gulf of Mexico and sub-tropics remain a trouble spot. The former, of course, being the location of interest for the oil business and the latter being relevant due to the Navy owing to the massive Norfolk Naval Station. It is doubtful that either will find great value in having extra notice of a storm that’s ten days to two weeks out at sea.

The National Hurricane Center and researchers will work aggressively on that problem, of course. This is but one part of their efforts to improve and expand the scope of forecasting. 7-day forecasts, with the accuracy of 4-5 day forecasts from a decade ago are another example of in-house work that is being prepared for future public consumption.

UPDATED 8 AM AUGUST 1

For the historical record, here are the first 5 day Outlooks

TROPICAL WEATHER OUTLOOK NWS NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER MIAMI FL 500 AM PDT THU AUG 1 2013 FOR THE EASTERN NORTH PACIFIC...EAST OF 140 DEGREES WEST LONGITUDE.. THE NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER IS ISSUING ADVISORIES ON HURRICANE GIL...LOCATED WELL TO THE SOUTHWEST OF THE SOUTHERN TIP OF THE BAJA CALIFORNIA PENINSULA. 1. SHOWERS AND THUNDERSTORMS ASSOCIATED WITH A LOW PRESSURE SYSTEM LOCATED ABOUT 775 MILES SOUTH-SOUTHWEST OF THE SOUTHERN TIP OF THE BAJA CALIFORNIA PENINSULA HAVE CHANGED LITTLE IN ORGANIZATION DURING THE PAST SEVERAL HOURS. THIS SYSTEM IS MOVING WESTWARD AT 10 MPH AND CONTINUES TO HAVE A MEDIUM CHANCE...50 PERCENT...OF BECOMING A TROPICAL CYCLONE DURING THE NEXT 48 HOURS. CONDITIONS ARE EXPECTED TO REMAIN MARGINALLY CONDUCIVE FOR DEVELOPMENT AFTER THAT...AND THIS SYSTEM HAS A HIGH CHANCE...60 PERCENT...OF BECOMING A TROPICAL CYCLONE DURING THE NEXT 5 DAYS. FIVE-DAY FORMATION PROBABILITIES ARE EXPERIMENTAL IN 2013. COMMENTS ON THE EXPERIMENTAL FORECASTS CAN BE PROVIDED AT...USE LOWER CASE... http://WWW.NWS.NOAA.GOV/SURVEY/NWS-SURVEY.PHP?CODE=ETWO FORECASTER AVILA ABNT20 KNHC 011132 TWOAT TROPICAL WEATHER OUTLOOK NWS NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER MIAMI FL 800 AM EDT THU AUG 1 2013 FOR THE NORTH ATLANTIC...CARIBBEAN SEA AND THE GULF OF MEXICO... TROPICAL CYCLONE FORMATION IS NOT EXPECTED DURING THE NEXT FIVE DAYS. && FIVE-DAY FORMATION PROBABILITIES ARE EXPERIMENTAL IN 2013. COMMENTS ON THE EXPERIMENTAL FORECASTS CAN BE PROVIDED AT...USE LOWER CASE... http://WWW.NWS.NOAA.GOV/SURVEY/NWS-SURVEY.PHP?CODE=ETWO $$ FORECASTER FRANKLIN/ZELINSKY

The disturbance mentioned in the Pacific Outlook is Invest 90, which is east-southeast of Hurricane Gil.

The Atlantic is quiet at this time and, as indicated by the Outlook, apparently for the foreseeable future. Note that there is a large outbreak of dust from Africa spreading across the tropics. But even before the dust storm, there wasn’t much of anything in the tropics. Go back three or four days and there was the remnants of Dorian and… not much of anything else. That’s not to say “and the usual assortment of tropical waves”. There was one wave just west of the Cape Verde Islands that was already sparse on convection before it was consumed by the dust surge. Now, there isn’t anything in the path of the dust to mow down or suppress. As Michael Watkins said in his tweets that were included in Brendan Loy’s post, the dust surges are annual occurrences and their suppressing effects are temporal. Furthermore, the suppressing effects of the Saharan Air Layer are a matter of debate. From the conclusion of “Reevaluating the Role of the Saharan Air Layer in Atlantic Tropical Cyclogenesis and Evolution“, a paper published in the June 2010 issue of the Monthly Weather Review:

The results of this study suggest that the SAL has perhaps been overemphasized by some in the

research community as a major negative influence on tropical cyclone genesis and evolution.

In fact, the evidence appears to be more to the contrary in that the Sahara is the

source of the AEJ, which acts as both a source of energy for AEWs and a source of strong

background cyclonic vorticity, and there is evidence of a positive influence through an induced

vertical circulation associated with the AEJ. To the extent that the SAL may be a negative

influence on storm evolution, one must recognize that the SAL is just one of many factors

influencing tropical cyclogenesis and evolution in the Atlantic. Each storm must be examined

carefully within the context of the larger-scale wind and thermodynamic fields (either from

global analyses or satellite data), particularly in terms of other sources of vertical wind shear

and dry air (i.e.,subsidence drying versus warming over the Sahara).

As such, it’s fair to say that it’s quiet in the Atlantic and that the SAL is the predominant feature at the moment. It may be a stretch, however, to say it is quiet because of the SAL.

UPDATED 11:00 AM August 3

Early verification of the first 5 day outlooks… the disturbance mentioned in the Pacific Outlook became Tropical Depression Eight, at this time. In the Atlantic, the remnants of Dorian were first mentioned in the 2:00 PM Outlook on August 1, with a 20% chance of development. Subsequent Outlooks took it up to 30%, then 40%, back to 30%, then jumped up to 50% in the 8:00 PM Outlook on Friday and then to 60% in the following forecast. At 5:00 AM today, the National Hurricane Center resumed advisories on Dorian as a tropical depression. The revival is expected to be quite brief, with the depression forecast to become a remnant low tonight.

“The Hurricane Season Forecast in its Proper Place”

June 10, 2013

I don’t read Communist publications very often, but when I do, I read about hurricanes.

While putting together last year’s hurricane season forecast compilation, I spent some time hunting for the primary source for the Cuban forecast. While I did not succeed in doing so, I did manage to find a gem of a column in Granma, the daily newspaper of the Communist Party of Cuba. Written by the head forecaster of Cuba’s weather service, Doctor Jose Rubiera, the article reminds its readers of the limitations of hurricane season forecasts. While I’ve seen National Hurricane Center directors and other such officials make some of the same points when they are quoted in articles reporting the release of a new season forecast, I’ve never seen anyone explain the matter in a direct manner as was done in this piece. Because of that, I found it worth the time to translate the column (a copy of which can be found in the original Spanish, here); any awkwardness is the product of my rusty translation skills.

The Hurricane Season Forecast in its Proper Place

When each new hurricane season draws near, and with it a new “Weather Exercise” *, everyone wants to know the forecast of hurricane activity that is expected for the season. In the National Forecasts Center of the Institute of Meteorology of our county, forecasts of hurricane activity in the Atlantic started to come out in 1996, the end product of a research project led by the researcher Doctor Maritza Ballester.

In the United States, the University of Colorado (sic) also puts one out as does the official weather service of that country, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The foreign media promotes these forecasts in a sensationalist manner, especially when the forecast calls for a high level of activity in the Atlantic.

It is precisely the massive disclosure of these seasonal forecasts, very different in essence from daily weather forecasts, along with very little explanation regarding what it’s really meant to say and its practical value, that promotes skepticism and frequent criticism of these forecasts.

It is easy for one to notice in a season that was forecast to be active, not a single hurricane affects land and thus think that the forecast was erroneous, when its actual meaning is different. Thus, with this article I wish to demystify a bit and also put in the place it belongs, the seasonal forecasts of hurricanes, for the purpose of better understanding.

The true value of the studies for the forecast of hurricane season lies in the science contained within, that is, the cognitive value of the study and unlocking the secrets of the oceanic-atmospheric conditions that are favorable or not to the appearance and development of tropical cyclones, and with that, an idea of the probability of hurricane activity.

Nonetheless, the practical value of the seasonal forecasts for the common person, their interests as such, is very limited, as they cannot say so many months beforehand (and nobody on earth can do it), where a storm’s path will be, nor of what force it will strike, how much rain it will bring, etc.

So, in practice, no one should use this type for forecast for themselves. It is only possible to know if there will be more or less tropical cyclones or hurricanes in all of the Atlantic, only this is attempted. Notice that in the large Atlantic basin, which includes the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico, there is a vast area that covers Cuba a thousand times over and a city or a specific point, perhaps millions of times.

In the practical sense, having an active, normal, or inactive season means little while the science cannot say exactly months in advance where, when, and at what force. I am going to give the example of the hurricane season forecast for 2012, put out a few days ago:

“The hurricane season will have normal to below normal activity. The formation of 10 tropical cyclones (tropical storms and hurricanes) is forecast, in all of the North Atlantic., 5 of which will reach hurricane strength. In the Atlantic Ocean region, eight tropical cyclones should develop, one would be in the Caribbean, and another in the Gulf of Mexico. The probability of a hurricane forming or intensifying in the Caribbean is low (15%) while that of a pre-existing one from the Atlantic entering the Caribbean (55%) is moderate.”

This assessment is based on the matter of fact that the existence and development of an El Niño in the summer months was forecast and these events produce strong winds at heights of 10-12 kilometers that cuts any incipient cyclone circulation and for this reason, inhibits formation of tropical cyclones in the Atlantic, though some manage to form. **Moreover, the waters of the eastern Atlantic are colder than normal, another factor that is unfavorable for hurricane activity. Research has shown these links, equal with others, whereas a statistical relationship and analogy with other seasons, produces the numbers released.

Nonetheless, see that just one hurricane, only one, passing through whatever location is enough for its residents to think the season is very active (and for them it is, in reality). examples abound, but I’m going to give only two. The hurricane season of 1930 was very inactive such that there was just one hurricane in the Caribbean… But that was of such great strength that it completely destroyed Santo Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic. Another example. The 1992 season was also inactive, only four hurricanes, but one was Andrew, a category 5 that devastated south Florida, United States.

There can also be the case of very active hurricane seasons, like those of 2010 and 2011 with 18 and 19 tropical cyclones respectively (the average or normal for a season is 10) or even better the very active season of 1995, which equaled the 20th century record with 21 cyclones, but in none of these seasons did Cuba have a hurricane.

To summarize, the Atlantic Hurricane Season Forecast indisputably has scientific value, to study the general conditions for formation and development of tropical cyclones, while supplying a probabilistic tool for certain activity; but it does not have a practical value for the general public as it cannot show with such advance notice the details that appear in the short-term forecasts that we always offer in the Early Alerts and the Tropical Cyclone Advisories.

The recommendation is that if you want to know the season forecast, there’s nothing wrong with that, just always interpret it for what it is, a measure of general hurricane activity, but when there is a tropical storm or hurricane already out there, everyone should be up-to-date on its path, evolution, and development via the radio and television and follow the guidance of our Civil Defense. This is the practical information that is truly valuable for effectively dealing with the threat of a hurricane.

* A annual two day hurricane readiness exercise conducted in Cuba prior to the start of the hurricane season. Spanish speakers can read the government’s description of the “Ejercicio Meteoro” here

** As one can see from reading the ENSO section of the verification of Colorado State’s 2012 hurricane season forecast, or any other season review, the Cubans were far from the only ones to think that an El Niño was going to develop. However, they did seem to put more weight on the probability of its formation than other forecasters did, hence the near 100% under-forecast of storm numbers.

Tropical Storm Andrea

June 5, 2013

With the entire hurricane season up to this point having passed with Tropical Weather Outlooks mentioning the possibility of its appearance, the first tropical cyclone of the season, Tropical Storm Andrea, formed late this afternoon.

While some forecast models hinted at the probability of the storm’s formation, it was never a sure thing due to relatively inhospitable atmospheric conditions; as late as 2 PM this afternoon, the National Hurricane Center gave the disturbance “only” a 60% chance of becoming a tropical cyclone.

Large totals of rainfall is the one thing that was a dead cert. Below is the anticipated rainfall totals for the next 48 hours, as forecast by NOAA’s Weather Prediction Center:

In the course of the past fifteen years in Florida, going back to the memorable summer of 1998, when ash on one’s car was a common sight and the Firecracker 400 was postponed to October due to wildfires, there have been many Junes in which residents have been dreaming of a scenario such as this. Alas, this is not one of them. For once, northeast Florida went into Summer with a normal amount of rainfall for the year, albeit unevenly distributed. Golf fans may recall that a month ago the iconic 17th hole at TPC Sawgrass was flooded. And that was not a particularly unique spot for flooding. Parts of rural Clay County (south-southwest of metropolitan Jacksonville), which thought they had seen the worst possible flooding last year in the wake of Tropical Storm Debby, found themselves facing even worse flooding. (A nice break-down of the heavy rain event can be found here). That event, combined with rain in advance of Andrea, creates a bit of a tricky situation for northern Florida. Fortunately, thanks to the recent experience with that event as well as Debby, people in the threatened areas should not find themselves surprised if/when flooding occurs. As was the case with Debby and (in a surprise) the nor’easter, the possiblityy of isolated tornadoes exists.

Take care of yourselves out there, my fellow folks in Florida, especially tomorrow night. Fortunately, Andrea will be yesterday’s news come Friday.

It appears that the only difference between Andrea and the nor’easter will be that one, Andrea will be immortalized forever, however minorly, in the history books. Such is the life for storms.

2013 Hurricane Season Forecasts

June 3, 2013

In addition to the review of storm names for the season, it is also my custom to post a summary of forecasts of activity for the forthcoming hurricane season.

If one reads over my posts from past seasons, there will find some of my misgivings and caveats regarding these forecasts. The purpose of the annual posts isn’t necessarily to highlight the forecasts as an uber-important piece of data. It is merely a convenient one-stop summary of forecasts for the season and those of the recent years past.

The forecasts I track here come from the universities Colorado State, Florida State,North Carolina State as well as NOAA, the United Kingdom’s Meteorological office, and the consortium Tropical Storm Risk. Note that is not the authoritative collection of forecasts; as the years have gone by more and more organizations release forecasts. The forecasts I’ve opted to follow are for reasons of long track record and easily accessible forecast verification (in the cases of CSU, NOAA, and TSR), notable performance (NC State in 2006), and parochialism (FSU, though as we shall see, its performance has justified its presence here). While my compilation of forecasts from past season may give the impression that the UK forecast is quite new, that is not the case; for a number of seasons they issued a July-November forecast that was incompatible for comparison with the other forecasts.

While some forecasts provide more predictions than others (with variance in how the numbers are presented), I’ve reduced the forecasts to core numbers. That is, single numbers for predictions of named storms, hurricanes, major hurricanes, and Accumulated Cyclone Energy. Note that for organizations that issue multiple forecasts over the course of a year, I’ve used the “final” pre-season forecast. As a sort of performance baseline, I’ve also included the trailing average of the previous 5 seasons for the forecast parameters.

Without further rambling, here are the forecasts for 2008-2012, with links to NOAA’s season summary for each year.

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Observed | 16/8/5 | 9/3/2 | 19/12/5 | 19/7/4 | 17/10/2 |

| 5 season trailing average |

17/8/4 | 17/9/5 | 16/7/4 | 13/7/3 | 15/7/4 |

| Consensus | 14/8/4 | 11/6/2 | 17/10/5 | 15/8/4 | 12/6/2 |

| CSU | 15/8/4 | 11/5/2 | 18/10/5 | 15/8/5 | 13/5/2 |

| FSU | 8/4/x | 17/10/x | 17/9/x | 13/7/x | |

| NCSU | 14/7/x | 13/7/x | 17/10/x | 15/8/4 | 9/6/2 |

| NOAA | 14/8/4 | 12/6/2 | 19/11/5 | 15/8/5 | 12/6/2 |

| TSR | 14/8/3 | 11/5/2 | 18/10/4 | 14/8/4 | 13/6/3 |

| UKMET | 13/x/x | 10/x/x |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Observed ACE | 145 | 51 | 166 | 127 | 128 |

| 5 season trailing avg | 160 | 154 | 119 | 102 | 111 |

| Con. | 139 | 76 | 177 | 148 | 97 |

| CSU | 150 | 85 | 185 | 160 | 80 |

| FSU | 65 | 156 | 163 | 122 | |

| NOAA | 136 | 85 | 186 | 140 | 95 |

| TSR | 131 | 69 | 182 | 124 | 98 |

| UKMET | 151 | 90 |

One misconception that some people have of these forecasts is that “every season is forecast to be above-average”. As one can see from 2009, when the inhibiting effects of the El Niño were correctly anticipated, that is not the case. It is the case, however, that we have been in an ongoing multi-decadal period of increased hurricane activity. As such, forecasts of activity, as well as actual activity, will be above-average. Relatedly, some think that when these forecasts fail, it’s because they consistently over-predict the level of activity and serve to “hype” the storm threat. The forecasts from 2012 show that to not be the case; everyone’s forecast under-predicted the level activity.

Something that one may note when reviewing these numbers is that there isn’t that much spread in the forecast numbers, especially in the case of storm numbers. There is a bit more appreciable differences in the forecasts for Accunulated Cyclone Energy. In its four seasons of existence, the forecast from FSU has had the most accurate ACE forecast three times (though it’s one failure was rather bad; it was the highest forecast in 2011).

Here are the forecasts for 2013:

| TS/H/MH | ACE | |

| 5 season trailing average |

16/8/4 | 124 |

| Consensus | 16/9/4 | 142 |

| CSU | 18/9/4 | 165 |

| FSU | 15/8/x | 135 |

| NCSU | 15/9/5 | x |

| NOAA | 17/9/5 | 150 |

| TSR | 15/8/3 | 130 |

| UKMET | 14/9/x | 130 |

As we can see, the forecasts are in general unanimous in the expectation of an active season; the consenus number of storms forecast matches the average of the past five seasons exactly. Again, one sees a bit of spread in the ACE forecast, Colorado State’s forecast is a fair bit higher than everyone else’s (though if one examines the range of numbers in NOAA’s forecast, it will be found that their “high-end” number is higher, yet). There’s a suggestion in the ACE forecasts that storms on aggregate will be a little more intense and/or longer lived than those of past seasons.

In general, forecasters do not see any obvious inhibiting factors for the season to come. Of the forecasts that have explicit input parameters (vice being based off a wide-scoped computer model), nearly all parameters therein are tilting to the plus side for storm activity.

As I mentioned earlier, there are many other forecasts besides these; the Washington Post’s Capital Weather Blog had a post that linked to many of the ones that I did not include here.

2013 Atlantic Storm Names

June 1, 2013

Here we are on June 1st, at the start of another hurricane season in the Atlantic. Per my (admittedly not quite reliable) tradition, here is my review of the storm names for the season. Where did these unfamiliar names come from? What happened to some of the familiar ones? The answers come out below.

This year’s list of names is the sixth iteration of the list first used in 1983. This list has had the most changes (total of 12) along with the most names retired from the original group (10). Owing to the low number of storms in 1983, there are only two names that have been used in each iteration . Two of the names have never been used and three are on the list for the first time. The names (with links for years to images of the tracking chart for the storm and links for retired names to the Wikipedia entry):

Andrea – This spot on the list was originally filled by Alicia, which was replaced by Allison in 1989. Allison, of course is the only tropical storm to have its name retired. Andrea debuted in 2007 as a pre-season subtropical storm off the southeastern United States.

Barry – In 1983, a category 1 hurricane that had made landfall (as a tropical depression) at Melbourne, Florida before transversing the Gulf of Mexico to make landfall in northern Mexico. Tropical storm at sea in 1989. Hit Nova Scotia as a tropical storm in 1995. In 2001, made landfall on the Florida panhandle, again as a tropical storm. The 2007 edition also paid a visit to Florida as a tropical storm before traveling up the east coast in a post-tropical life.

Chantal – Category 1 hurricane at sea in 1983. The 1989 version struck Texas and was responsible for 13 fatalities (all due to drowning, the sad details can be read here). Tropical storm at sea in 1995 and in the Caribbean in 2001. The 2007 edition was a short-lived tropical storm that caused flooding in Newfoundland in its post-tropical life.

Dorian – New for 2013. Replaces the monster of the 2007 season, Dean.

Erin – Category 2 hurricane at sea in 1989. Made landfall near Vero Beach, Florida as a category one hurricane , crossed the peninsula and made a second landfall near Fort Walton Beach as a category 2 in 1995. In 2001 it was an “interrupted-track” storm that eventually became a category three hurricane and passed just east of Bermuda and later Cape Race, Newfoundland (in its final hours as a tropical storm). The 2007 edition struck Texas as a tropical storm and the remnant low persisted into Oklahoma and strengthened briefly;the storm report has a paragraph on why the NHC did not consider it to be a tropical cyclone over Oklahoma despite its convective organization and relatively high winds.

Fernand – New for 2013. Replaces the name of the other category 5 hurricane of 2007, Felix.

Gabrielle – Category 4 hurricane at sea in 1989. Small tropical storm into northern Mexico in 1995. The 2001 edition caused a fair bit of flooding in Florida after making landfall on the west coast near Venice before re-intensifying to a category 1 hurricane in the Atlantic. In 2007, the name was attached to a short-lived tropical storm that affected the Outer Banks of North Carolina.

Humberto – Added to the list in 1995, replacing Hugo. The debut edition was a Category 2 hurricane as was the subsequent 2001 storm. In 2007, formed from the remnants of the same front that spawned Gabrielle. It went from tropical depression to hurricane in less than 19 hours and was rapidly strenghening prior to landfall at High Island, Texas.

Ingrid – Replaced Iris after the 2001 season. Inauspicious debut in 2007 as a weak and short-lived tropical storm.

Jerry – Hit upper Texas as a category 1 hurricane in 1989 . The 1995 version affected central Florida as a tropical storm. 2001 and 2007 editions were fairly short-lived tropical storms.

Karen – Loopy tropical storm in the western Caribbean in 1989. Tropical storm at sea in 1995. Was a category 1 hurricane in 2001 before making landfall in the Canadian maritimes as a tropical storm.

Lorenzo – Replaced 1995’s Luis. Tropical storm in 2001. Quick forming category 1 hurricane that struck Veracruz, Mexico in 2007.

Melissa – Replaced 2001’s Michelle, which was a one time replacement for Marilyn. Was a short-lived tropical storm just west of the Cape Verde Islands in 2007.

Nestor – New for 2013. Replaced Noel, a category1 hurricane that was directly responsible for no fewer than 163 deaths at the end of October 2007.

Olga – Replaced 1995’s Opal. A wayward category 1 hurricane at sea in 2001. Made an east-west crossing of Hispanola as a tropical storm in post-season 2007, causing 40 deaths along the way.

Pablo – Only appearance was in 1995 as a weak tropical storm.

Rebekah – Replaced Roxanne in 1995, but is yet to debut.

Sebastian – Tropical storm in 1995 that hit the island of Anguilla before dissipating in the Caribbean.

Tanya – Was a category 1 hurricane in 1995 before striking the Azores as a tropical storm.

Van – Never used.

Wendy – Never used.